History

Explore our past! Read about our founding, the fight for fair wages, safe working conditions and how we grew to 20,000 members during WWII.

The First International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers Local Union Halls

The first two IBEW Locals established in Portland were Local 317, chartered in 1904, and Local 480, chartered in 1912. These two Locals elected to merge in May 21, 1913, to form a unified Local Union. Since 1913, Local 48 has increased the standard and quality of living for thousands of electrical workers, helping them achieve decent wages, improved working conditions, and the right to organize. Local 48 has helped maintain and increase the honor and dignity of hard work in organized labor, while earning respect outside of the labor movement.

IBEW Local 48’s First Business Manager

Our first Business Manager, ‘Mud’ Crockwell, signed contracts with local electrical contractors which called for a wage of 22¢ an hour, a six-day work week for journeymen, and a dollar a day for their helpers. By World War I, Local 48 was able to negotiate a 40-hour workweek and time-and-a-half for overtime. Hard times followed the War, with non-Union shops pitting one man against the other for less pay and longer hours. During this turbulent period, Local 48 and its Business Managers continued to work with electrical contractors to develop a sound relationship. In the 1920’s, Local 48 included a no-strike clause in its agreements that helped stabilize Union shops and gave us an edge over non-Union shops.

Local 48 weathered the tough times of the Depression even though many members couldn’t afford their Union dues. Through their personal sacrifices, members committed to the Union and kept it alive. With the start of World War II, the tide of work changed Union members found plenty of work with the defense industry. Shipbuilding in the Portland area increased membership, including many women, to over 20,000–making Local 48 the largest Union in the nation.

Committed to Electrician Apprenticeship Training & Education

In the years following the War, Local 48 began its commitment to education–which today has produced one of the top-ranked apprenticeship training programs in the nation. Our program, in conjunction with the Oregon-Columbia Chapter of the National Electrical Contractors Association, serves as a model for training programs around the world. During the 1960’s and 70’s, Local 48 benefited from the construction boom, with members working on some of the area’s most important projects. The boom ended in the 1980’s with a recession. Still, Local 48 leaders had a Vision for the Future. They worked together with NECA to put in place new programs and new opportunities that brought about positive changes for Local 48 and its electrical contractors.

Today, Local 48 enjoys a nationwide reputation for excellence and productivity as the Portland area once again is experiencing growth in the building industry. Our journeymen are the best trained and most up-to-date in the nation. Their state-of-the-art skills, journeymen are employed on projects all over town–from safe wiring for family homes to the most intricate high tech projects.

Pages From Our Past

For more than 100 years, members of IBEW Local 48 have gathered, like this crew from Dimitre Electric back in 1965, for a traditional group shot celebrating the completion of a project. This Dimitre Electric crew was particularly proud of their remodel of the old Multnomah Hotel, now long gone from the Portland scene.

Pages From Our Past celebrates our competence, our safety record, and our industriousness and efficiency. The vignettes collected here recount slices of our long proud history. They tell us who we are and perhaps more importantly, where we’re going as an organized community of highly skilled union electricians dedicated to improving the world we live in. It’s our story.

1893: “Where did ‘48’ come from?”

During their Labor Day picnic in 1903, members of “I.B. Electrical Workers Local Union No. 48” in Shawnee Indian Territory

(today, the eastern half of Oklahoma), posed for this group photo.

This gang won a prize of $25.00 in a tug-of-war with the carpenters’ union.

[Source: The Electrical Workers’ Journal for April 1952, page 89.]

We weren’t the first “IBEW Local Union No. 48.” Portland wasn’t even the second IBEW local to be assigned the number 48. In fact, the International assigned 48 to five different union charters before the number found its home in Portland.

The six IBEW union locals assigned the number 48 included the following:

| City/State | Charter Date | Final Activity |

| Sedalia, Missouri | June 3, 1893 | September 3, 1893 |

| Decatur, Illinois | January 25, 1898 | October 12, 1898 |

| Milwaukie, Wisconsin | April 19, 1899 | June 1899 |

| Richmond, Virginia | February 14, 1900 | September 1905 |

| Shawnee, Oklahoma Territory | October 1, 1905 | June 1907 |

| Portland, Oregon | May 21, 1913 | Present |

[Source: Appendix contained in the “Report of International Secretary Jack F. Moore,” distributed to attendees at the 35th International IBEW Convention in 1996.]

The number 48 found its permanent home in Portland when International recognized the charter of IBEW Local 48, signed by the 14 original members on May 21, 1913.

The International had to reassign the number 48 for a variety of reasons. In some cases, anti-union sentiment forced a local out of existence. Other times, an economic downturn killed off a local. Union rivalries had an impact, too, as was the case in Portland. The assignment of the number 48 to the new union came after several years of internecine squabbling over money and jurisdiction by rivals IBEW Local 317 (chartered on August 1, 1904) and IBEW Local 480 (chartered June 11, 1912).

Later in the 20th Century, IBEW Local 48 merged with other IBEW locals in the region as local economies transitioned from forest products, agriculture or fisheries to high technology. Local 48 retained its number with its merger, in 1972, with IBEW Local 517 in Astoria, Oregon (chartered 1906), and again with its merger, in 2012, with IBEW Local 970 in Kelso-Longview, Washington (chartered in 1924).

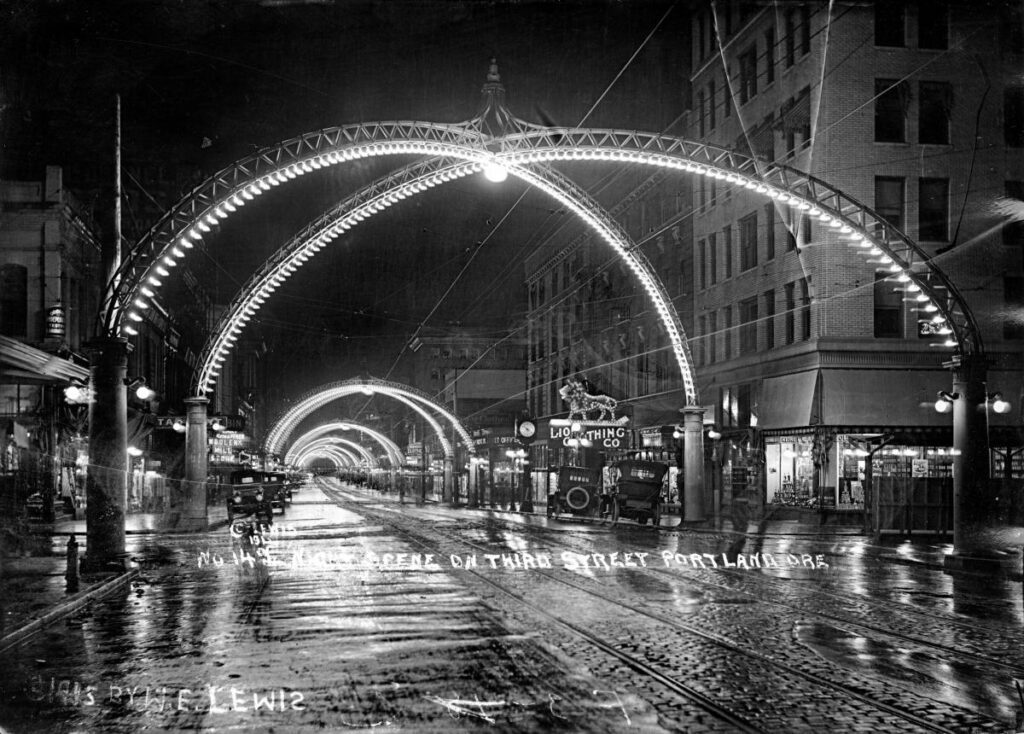

1914 – “Local 48 Constructs The Great Light Way”

Few Portlanders had ever heard of us here at IBEW Local 48 a century ago. But that changed overnight, back in the summer of 1914. We lit up the night sky, turning 10 blocks of Third Street into “The Great Light Way.”

The warm night air pulsated with the ragtime music of Campbell’s American band. Thousands of excited Portlanders lined both sides of Third – from Yamhill to Burnside – in front of Lion Store and Powers, H.T. Hudson Arms Co. and W.H. Dedman’s cigar shop.

Suddenly, at 8 p.m., Saturday, June 6, 1914, an employee of Northwestern Electric (predecessor of Pacific Power & Light) threw a ceremonial switch. Instantly, thousands of light bulbs blazed from double arches over every one of those 10 intersections of Third Street. “Ooooooohs!” and “Aaaaaaahs!” filled the warm night air.

The incandescent burst of light made “The Permanent Order of Third Streeters” and all the shoppers in their stores feel like this was the center of business in Portland. Third Street was even brighter than Broadway!

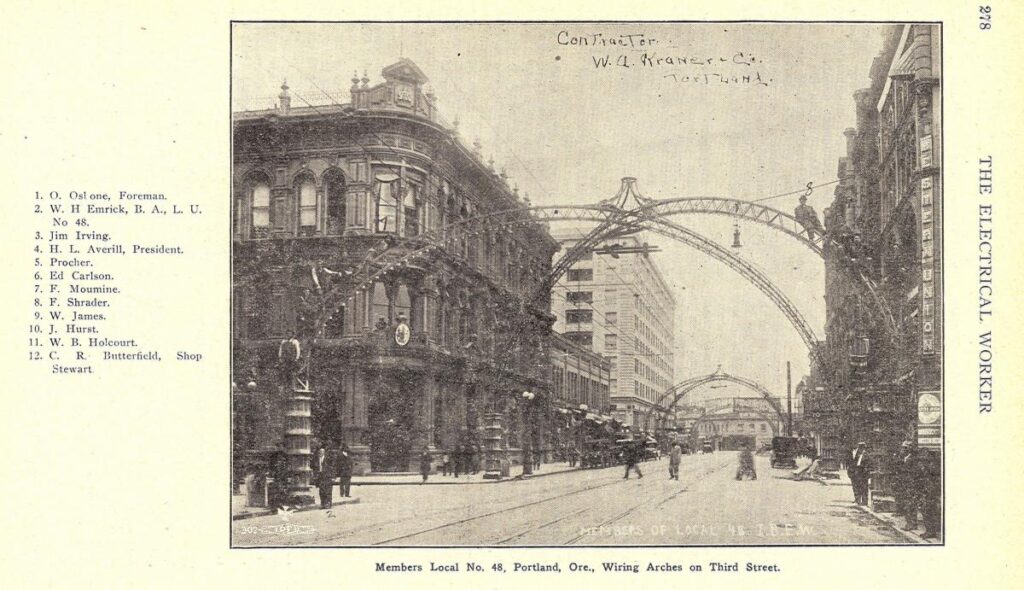

And who built The Great Light Way? IBEW Local 48 contractor W.A. Kraner & Co. and union electricians, Jim Irving, Ed Carlson, F. Moumine, F. Shrader, W. James, J. Hurst, Andy Peacher and W.B. Holcourt.

The photo, above, of the original 12-member IBEW Local 48 crew proudly perched on top of the massivearches over each intersection of Third Street, appeared on page 278, the centerfold, of the June 1914 issue ofthe IBEW’s official journal, The Electrical Worker.

They used a special derrick truck to erect the double arcades. Under the supervision of Local 48 Business Agent, W.H. Emrick, President H.L. Averill, Shop Steward C.R. Butterfield, and Foreman O. Oslone, the electricians wired each pair of intersecting arches of latticed steel. The Local 48 crew anchored the arches at each street crossing in Doric columns of concrete. The crew bent pipe and ran wire to ninety-six 40-watt bulbs on each of the pairs of arches, and crowned each intersection with a blinding 750-watt nitrogen lamp. Their work on The Great Light Way would light up Portland for a quarter century.

Then the Depression hit and times started to change. In 1931, Portland City Ordinance No. 61325 re-christened the street Third Avenue. The Great Depression and Northwestern Electric’s $6,700 annual light bill killed off The Great Light Way, in 1937. Demolition began soon after. In 1947, Northwestern Electric also disappeared, merged into Pacific Power.

However, we electricians of Local 48 would not only survive the Depression but, later on, prosper, working hand-in-glove in relative harmony with NECA contractors into the 21st Century!

1915: “Local 48 Revolutionizes Portland’s Retail Industry”

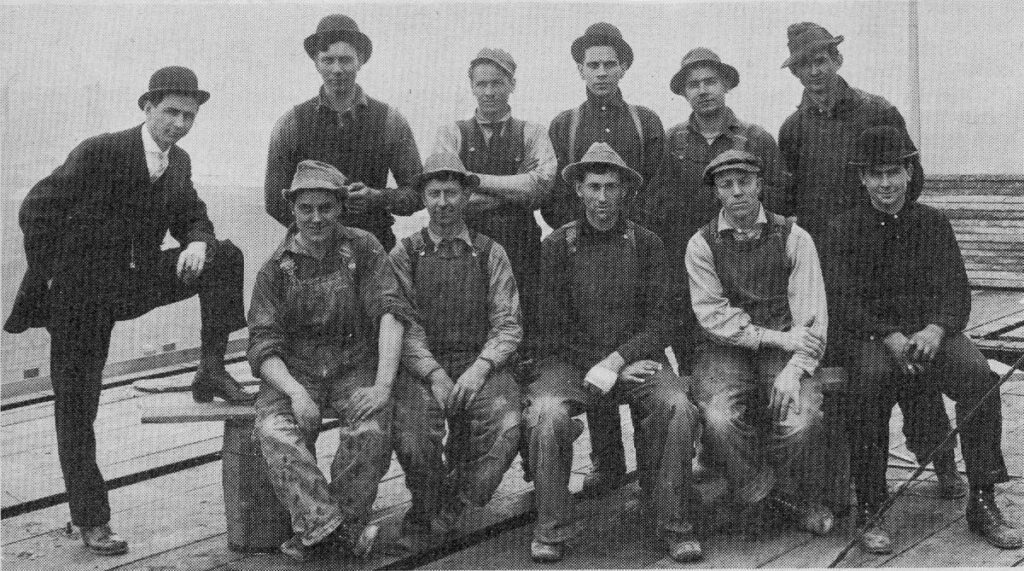

Topping out after wiring the “new” Meier & Frank department store.

Our union was only two years old when this historic photo was snapped in 1915. The picture shows 10 members of Local 48 as they “topped out” after wiring the new 15-story Meier & Frank Department Store in downtown Portland. They effectively revolutionized retail shopping by departments that were layered, one floor on top of another, in a skyscraper accessible by electric elevators and escalators. Without the craftsmanship of members of IBEW Local 48, Meier & Frank shoppers would have had to hike a dozen flights of stairs to Menswear – impossible!

The fellow standing on the back row, second from the right, was Clinton Smith. He served several terms as Local 48’s president.

The man in the bowler hat on the left in the photo above was job superintendent J.H. “Harry” Sroufe. He would later form Jaggar-Sroufe Co. with Samuel I “Bud” Jaggar. Jaggar had turned out as a journeyman in 1904 when he helped wire 3,000 light bulbs in the Forestry Building at the Lewis and Clark Exposition, and who, in 1907, formed what was likely the first union contractor firm in Portland, Morrison Electric Co.

Jaggar-Sroufe made history as the first employer in our industry to reduce the workweek from 48 to 40 hours. This was no small feat considering it was an era of labor unrest, the Wobblies, and strike-busting “Red Scare” riots with organized labor across America experiencing a rising tide of anti-unionism. But our union brethren didn’t look that worried. Why? Is it possible that their smiling, self-satisfied expressions portended a harmonious partnership between IBEW Local 48 and the Oregon-Columbia Chapter of NECA? Fifty years later, Local 48 President John Clothier delivered the answer to that question.

The occasion, on November 2, 1963, was our union local’s 50thanniversary celebration. More than 720 Local 48 members and their wives attended the gala in the Sheraton Hotel. Jaggar, who was still very much alive, applauded two of the original signers of IBEW Local 48’s charter in 1913, Andy Peacher and Homer Gifford. W.R. McCabe, president of the Oregon-Columbia Chapter of NECA lifted a glass in tribute to H.H. “Hub” Harrison who had retired several months earlier after serving as IBEW Local 48’s business manager since 1948.

It was a night to remember. So a kid named Eddie Barnes, who 20 years later would be elected business manager of Local 48, published news of the 50th Anniversary gala in the April 1964 issue of IBEW’s Electrical Workers’ Journal. In his story, Barnes quoted Local 48 President Clothier as follows:

“The gains in wages, welfare and working conditions have been reached under agreement with the National Electrical Contractors Association, Columbia Chapter, with whom we have worked in harmony as attested by the absence of a strike in the past 43 years.”

“Golden Jubilee” remarks by John Clothier

Portland Sheraton Hotel, Portland, Oregon

November 2, 1963

Today, 50 years after Clothier’s toast to the NECA/IBEW Local 48 partnership, and 100 years after the historic “topping out” photo at Meier & Frank, we’re still working in uncommon harmony with our NECA contractors.

The future of our union in 2015 remains as bright as the lights in the 13 floors of shopping departments in that Meier & Frank Department Store back in 1915. Membership and training in 2015 is an unparalleled opportunity for young people seeking a trade that is as essential today as the iconic Main Floor clock, and the elevators and escalators were in Meier & Frank a century ago.

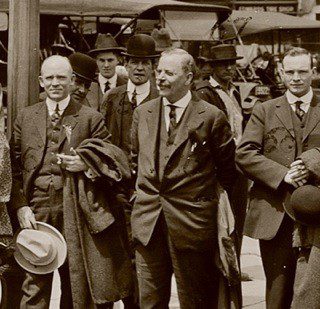

1916: “Who was “Mud” Crockwell? (And where did he get that name?!)”

“Mud” Crockwell, center, in bowler hat.

On June 28, 1916, “Mud” Crockwell’s image was captured in the rear of a group photograph of the Oregon Association of Electrical Contractors and Dealers (predecessor of NECA) at S.W. Sixth and Pine streets in front of Stubbs Electric. He is wearing a bowler hat and smoking a cigar. For the past 50 years, Crockwell has been referred to as the first business manager and financial secretary of IBEW Local 48. But was he?

Speakers at both the 50th and the 75th anniversary celebrations of IBEW Local 48, in 1963 and 1988, referred to John Daniel Madeira “Mud” Crockwell’s negotiating accomplishments as Local 48’s first business manager. Local 48’s website and numerous union histories listed him that way. His name was listed under an empty picture frame in the lobby of Local 48, alongside framed photos of most of the subsequent business managers. Unfortunately, historical evidence suggests otherwise.

“Mud” was likely shorthand for Crockwell’s middle name, Madeira, pronounced muh-dair-uh. Crockwell was born October 17, 1878, in Salt Lake City, Utah, and moved to Portland with his mother, brother and other family at the turn of the century. Newspapers of the day referred to him as a hard-driving organizer for IBEW Local 317, which was chartered in 1904. His brother Frank was president of the local.

In March 1908, The Electrical Worker referred to Crockwell as financial secretary and business agent of Local No. 317. Crockwell was cited for his initiative by Local 317’s press secretary, D.B. Brooks, for organizing the “picture machine” operators.

In September 1908, The Oregonian editorialized against Crockwell and two other union men, C.M. Rynerson and W.H. Fitzgerald, for their “impudence” in publishing a “manifesto” for the election of William Jennings Bryan for president of the United States, implying that their advocacy for a political candidate was somehow a violation of labor unionism.

Crockell was known at city hall as a union electrician with strong opinions about Portland’s new building codes. Indeed, at one time Crockwell’s opinion so infuriated the Electrical Code Committee (of which he was previously a member) that they “denounced” Crockwell in a statement to the Portland City Commission for his “attacks” on a proposed code requirement that would have required bonding of all contractors and electricians.

He was popular among the more than 100 members of Local 317 and a brother to the other trades. He organized the big Labor Day picnic at Oaks Amusement Park. In July 1909, The Oregonian reported Crockwell was elected to a six-month term on the Central Labor Council [Building Trades Council] as one of its reading clerks, representing Local 317 electrical workers. He was also elected to the local ministerial association.

In 1908-1909, Portland was about as far away as a member could get from the politics of the International IBEW. Nevertheless, reports started filtering into Local 317 that Frank J. McNulty, president of the International, and Peter W. Collins, the secretary, were engaged in a bitter, internecine fight over control of union funds with a rival faction led by J.J. Reid, president, and J.W. Murphy, secretary. The International’s fight reverberated in Portland.

Some of the members of IBEW Local 317, led by the Crockwells, sided with the Reid-Murphy, according to The Electrical Worker. Other members of Local 317 remained loyal to McNulty-Collins, and in 1912, sought recognition from the International, which temporarily designated them as IBEW Local 480.

In 1911-1912, Samuel Gompers, president of the American Federation of Labor, sided with the McNulty-Collin faction. The bruising contest at the International level spilled over into the workplace in Portland. Local 317 and Local 480 members started competing against each other. Finally, in 1912, the courts decided in favor of McNulty-Collins faction and gave them control over the union funds.

A few months later, the Portland Building Trades Council threw members of the “Reid-Murphy” Local 317 off the council. On May 21, 1913, fourteen electricians signed the charter for creation of IBEW Local 48. Crockwell’s name was not among them. Competition persisted between the members of the old Local 480 and the “Reid-Murphy men” of the old Local 317, who offered to work for $0.50 per hour less than scale. Gradually, the tone softened. In March 1914, the new Business Agent, W.H. Emerick, announced in The Electrical Worker that the memberships of Local 480 and Local 317 were now merged into IBEW Local 48. Andy Spice was financial secretary.

But what of Crockwell? His name pops up many times after 1913, in public records, military draft registrations for World War I and II, and in The Oregonian, but never as business manager or even as a member of IBEW Local 48.

In 1916, he was a member of the Multnomah County Clerk’s staff. Two years later, at the age of 39, Crockwell’s World War I draft registration listed him as an electrician employed by NePage-McKinney Co. He had many other callings the next 40 years: community organizer, advocate for retired public employees, checker for the Oregon Liquor Control Commission, advocate for the elderly and the Multnomah County “Poor Farm” in Troutdale, and a member of the South Mount Tabor Improvement Association. But never again was he listed as the business manager, agent or financial secretary of an IBEW local. He ran for public office several times, as a Portland City commissioner, Multnomah County Auditor and Multnomah County Commission, but never won.

Crockwell died January 17, 1960, and was buried in Lincoln Memorial Park after funeral services Friday, January 29, 1960, at A.J. Rose & Son Mortuary.

934: “Local 48 Electrician Roams America!”

S.P.A.C. BX Armor-Cutting Pliers

This is curious. Why in the world is a pair of Utica Tools “BX100 Armor-Cutting Pliers” on display in the foyer of the NECA/IBEW Electrical Training Center? They’re old, outdated, and frankly don’t fit the image of the 21st Century inside electrician of Local 48.

But consider this: One of us invented the pliers!

His name was Clinton E. Smith. Back during the Great Depression of the 1930s, journeyman Smith found a use for his downtime at Milwaukie Electric Co. He invented and then named these pliers, “S.P.A.C.”. In 1934, the U.S. Patent Office issued him Patent No. 1,970,983. This is where the story gets interesting!

The competition was tough – Klein Tools and other toolmakers were well entrenched and much favored by electricians. But Clinton E. Smith believed in himself and his S.P.A.C. pliers. And if you haven’t figured it out yet, S.P.A.C. stands for Smith’s Pocket Armor Cutters.

Thanks to the April 1936 issue of the IBEW’s Journal of Electrical Workers, below, we can piece together his “marketing plan.” In his own words, on page 168, Smith’s plan was to roam the United States, from one IBEW local to another, selling his pliers. It was no small feat considering the country was enduring the Great Depression. Almost a quarter of our nation’s workforce was unemployed. Who had the money to buy a pair of pliers? That didn’t stop Smith – and he left no record whether his wife Carrie thought his plan hare-brained.

First step was to forge 1,000 pairs of pliers. On Wednesday, April 18, 1934, Smith loaded them in his sagging Model T Ford “jalopy,” blew a kiss to Carrie, waved good-bye to son Harold, and said farewell to his daughter Helen. At the age of 48, Smith backed down the driveway of his 2513 Lake Road home in Milwaukie, Oregon, and struck out for the Cascade Range and a mighty bumpy drive through the Blue Mountains to Salt Lake City. It was to be the trip of a lifetime.

Smith put that Model T to the test. He visited IBEW local unions halls all along the way, peddling pliers in Omaha, and then Chicago, and dozens of other cities.

“In many locals along the line, my (IBEW union) card surely helped me across,” said Smith in the Journal article published two years after completing his road trip. “As many of the boys read this, they will recall meeting me and I want to say everyone treated me fine. I sold tools as I traveled.”

Smith saw the nation on its back. Times were hard. Some union electricians had trouble paying their dues. Smith heard it all, and saw it too, yet he wrote with optimism for the future.

“Things were pretty dead all over but I sold a lot of BX cutters,” said Smith.

Roads were poor. Smith’s Model T gasped under its load of S.P.A.C. pliers for cutting BX and BXL Nos. 12 and 14, two- and three-wire, and also flex steel.

“Yes, I had plenty of trouble with the old Henry. She was a home car and did very well here on short hauls but when I put that baby on the road she started going haywire,” said Smith. Shortly after he crossed the New York state line, the Ford quit cold in Rochester, forcing Smith to trade in for a Chevy coupe.

He drove to New England, and feared for his life on his drive from Boston to New York City on the old Post Highway.

“. . . [W]hat a highway, and do they go! I saw some pretty bad wrecks on my travels but luckily for me I was not in any of them,” said Smith.

Weather was a constant threat, especially on dirt roads.

“They say it rains here in the West, but listen, Brother, the rains we have here are only showers compared to what they have in New England. I nearly got drowned in Rhode Island . . . .”

Smith crossed the most famous rivers in America “at from a dime to a dollar a throw.”

He battled heat in Newark, N.J., where he “got a room there at a hotel, went to bed with an electric fan and a bucket of ice water and slept ‘raw’ all night.”

He climbed all 557 steps of the Washington Monument, saw the tomb of the Unknown Soldier, crossed the Potomac into Virginia, and cut his way through the Deep South for Miami. Which is where he discovered mosquitoes.

“Say, listen, Brother, they’ve got mosquitoes through the South that can stand flat-footed and eat out of a candy bucket. Believe it or not, and when they bite, they sure leave a trade mark,” said Smith.

With his BX cutters pretty well introduced, Smith yearned for home. He re-crossed America, this time through the lower Midwest including Kansas, the state of his birth, through Colorado, Wyoming and Idaho, finally down the now-historic Columbia River Highway to his home in “good old Oregon.”

Smith turned over manufacturing and sales of his S.P.A.C. product line to Utica Tool, “glad to be back” in his shop at Milwaukie Electric. His parting words to his union electrician brethren, nationwide were, “I want to thank all the boys for using these tools and helping me to introduce them.”

Smith died in Portland on October 23, 1969. He was 84.

1942: “Female ‘Firsts’ in Local 48”

Journeyman Ann Bruce

Change is hard. No doubt. But since it was a matter of life or death for our nation, IBEW Local 48 decided to admit its first female into the union. She was Ann Bruce. She started work on her birthday, April 30, 1942. We were under attack from Imperial Japan and Nazi Germany. Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, Commander in Chief of the U.S. Pacific Fleet, appealed to his fellow Americans, “I ask your help. On behalf of all your fighting sons, brothers and husbands whom I command in the Pacific, I ask that every skilled man and woman in America who can work in a shipyard [to] volunteer immediately.”

Hundreds of thousands of men and women poured into military service. That left the trades bereft of skilled craftsmen. Who would answer Admiral Nimitz’s cry for help to win the war? Bruce and other women, as well as other minorities, that’s who!

Bruce’s husband was an invalid. She had a six-year-old daughter. She could use the income and liked working with her hands. She needed training, and so arranged for childcare and took courses in aviation sheet metal and marine wiring. Bruce went to work at Oregon Shipbuilding Corporation, the first shipyard in the country to hire women workers. She was likely the first woman admitted to IBEW Local 48. She wouldn’t be the last. She was the first woman in Oregon to receive a journeyman lectrician’s card, according to the International Brotherhood.

“I’ve never worked with a finer bunch of men and have never done anything in all my life that I like so well,” Bruce said in “Kaiser Yards Founded on Union Cooperation,” published in the November 1942 issue of the IBEW’s The Journal of Electrical Workers and Operators.

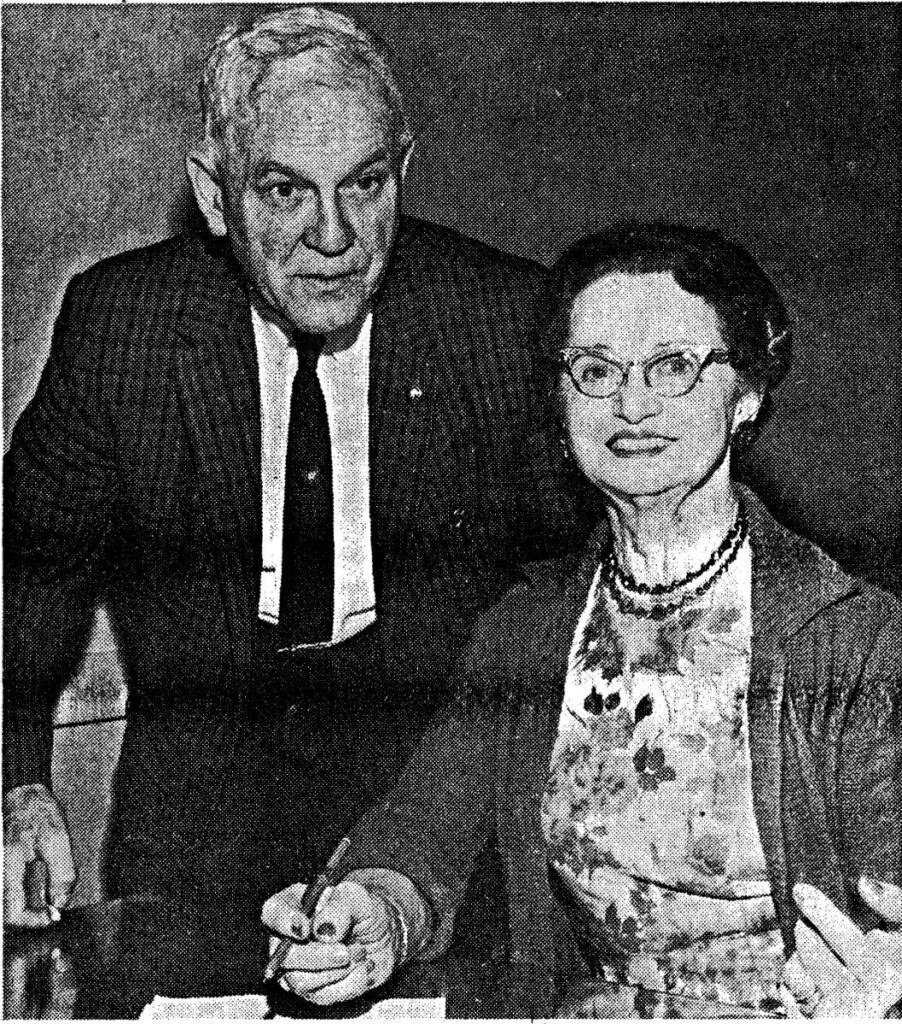

Marie Gleason in 1962

Another shipyard electrician who achieved the status of journeyman was Marie Gleason. She achieved “first in the nation” status in 1962 when Local 48 Business Manager Hub Harrison, pictured with her in the Oregon Labor Press photo to the right, signed her up for her pension. Gleason was he first female among 17,000 men to earn full benefits under IBEW’s retirement plan.

Gender played no role when Local 48 hired its first manager of its newly chartered Federal Credit Union, in 1954, a female named Lois Burnside.

NECA/IBEW Local 48 created an “equal opportunity” gateway into the electrical industry in 1963, forming a Joint Apprenticeship and Training Committee (JATC).

The first female to turn out as a journeyman in the postwar era was an African American Charlene Molden. She began her apprenticeship in 1973, blazing the way into the trade for other

women to follow. Dozens of other women would likewise gain their journeyman’s ticket before the end of the decade.

Keith Edwards, a trailblazer himself as the first black business manager of Local 48, recalled “Charlye” for her high-spirited grit. She endured what today might be regarded as sexual harassment but her response was to give as good as she got.

“We had a job shack, and back then the guys put Playboy pictures up on the wall. She said she had a problem with that. They said, ‘Ah, too bad.’ So, she went and got some Playgirl pictures and put them up on the wall. All the Playboy pictures came down,” said Edwards.

Nancy Bock

Nancy Bock got involved in the Local 48 leadership, becoming the first female journeyman elected to the Executive Board where she served as recording secretary in 1986 and later as vice president in 1989. Bock ran on a platform of prosperity for members as a way of promoting diversity and equality.

Other women won awards as valued employees, community volunteers and recognition for their just plain hard work, many of them “first” in their role. In 1984, women JATC grads comprised 20% of the electricians hired by McCoy Electric to renovate the historic Paramount Theater. In 1987, EC Company selected JATC graduate Sandra Carr as its “Outstanding Electrician” from among 160 employees. In 1993, JATC hired Nancy Mason to diversify programs. A year later, of the 714 applicants for JATC, 9.8% were women, 17.2%, minorities. The trend continued in 1999 with JATC’s move to a new $6 million NECA/IBEW Electrical Training Center (NIETC).

In 2007, following his election as business manager, Clif Davis hired Nancy Cary as the union’s first female business representative and Donna Hammond, its first black female business representative.

Bridget Quinn accepting “Women of Vision” award

In 2011, NIETC training director Rod Belisle recruited Bridget Quinn as the first female Workforce Development Coordinator. Belisle assigned Quinn, a Local 48 journeyman electrician with shop steward experience working for Dynalectric Oregon, to reach out to women and minorities who were curious about the trade but who had no friends or relatives in the union.

“I think the greatest barrier has been that a lot of these folks don’t come from a community with a big construction background. If you don’t see somebody or know somebody growing up who works in the construction field, then you don’t think of it as an option. Later on down the road, they can be role models for their siblings or community,” Quinn said. In the summer of 2014, Quinn won the Daily Journal of Commerce “Women of Vision Award.”

Today, IBEW Local 48 is a union of brothers and sisters. We’re seeing multigenerational family membership among both women and minorities. That’s a sure sign of increasing, and irreversible, diversity. The tradition today includes Daniel Ramirez who followed his mother Marjorie Ramirez into the electrician’s trade at Local 48. In this role, Ramirez certainly was first, as was Ann Bruce the union’s first female journeyman electrician back in 1942. And like Bruce, Ramirez won’t likely be the last woman to achieve such a distinction.

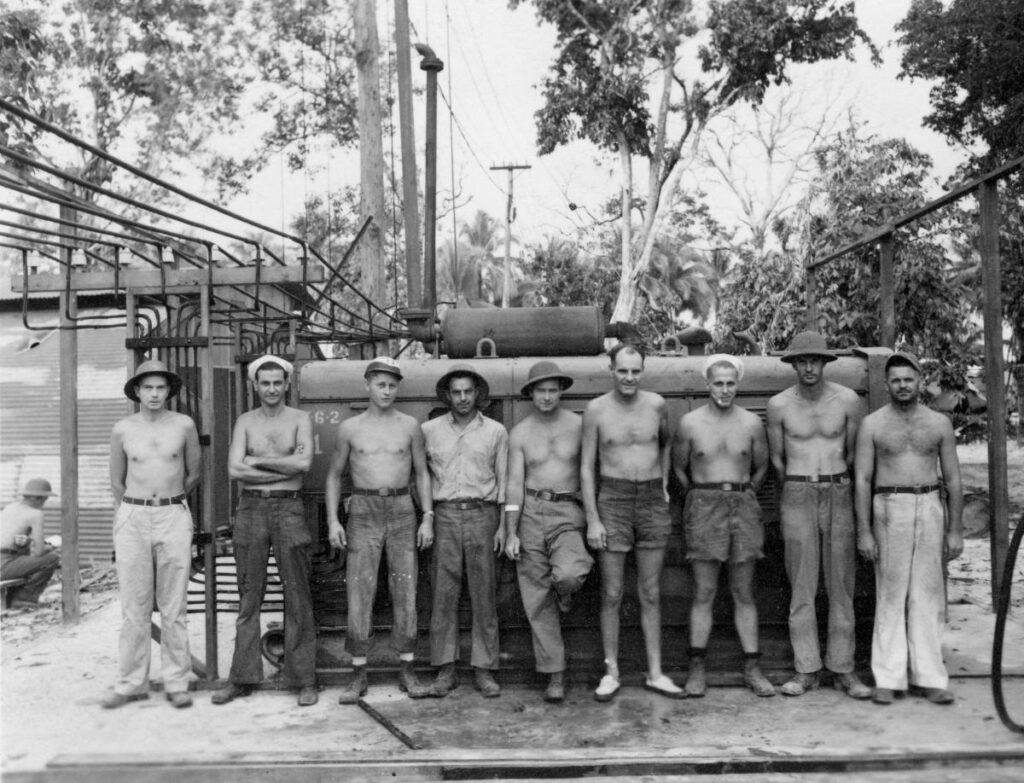

1944:”IBEW Local 48 Goes To War”

IBEW goes to war in the 55th Naval Construction Battalion.

World War II was drawing to a close when Electrician’s Mate First Class C.M. Stehman mailed this 1944 photo to IBEW Local 48. The union published it in the February 1945 issue of IBEW’s Journal of Electrical Workers and Operators. In the story accompanying the photo, the union noted that “L.U. No. 48 thinks that all of these boys look mighty fine and fit and is very proud of them all and the whole I.B.E.W. joins Local 48 in that feeling.”

Stehman was a member of IBEW Local 48 when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. Three days later, Nazi Germany declared war on the United States. The nation mobilized. The ranks in Portland of veteran NECA contractors and journeyman electricians in IBEW Local 48 thinned out. Stehman was one of those who left Portland for war in the Pacific. This created opportunities for women and minorities, especially in Portland’s six shipyards, and would forever change the complexion of Local 48 and shape the character of the union to this day.

Stehman, third from the right in this official U.S. Navy photo above, was important if only because he was typical of thousands of journeyman electrician members of IBEW Local 48 who for the past 100 years have answered our nation’s call to military service.

The Navy assigned Stehman to the Pacific Seebees. They would endure mud, sweat and malaria in New Guinea in the 55th Naval Construction Battalion, happy to survive. His particular “band of brothers” in the photo above included (L to R) George Bixley, IBEW Local 643, Carlsbad, New Mexico; Elmo Morrissey, IBEW Local 340, Sacramento; Henry C. Anderson, IBEW Local 77, Seattle; Roger V. Williams, IBEW Local 1025; Harold D. Henderson, IBEW Local 125, Portland; R.E. Stephens, IBEW Local B-11; C.M. Stehman, IBEW Local 48; Maynard Atterbury, IBEW Local 659, Central Point, Oregon; and Herbert L. Shanks, IBEW Local 728.

As with most veterans called up for service to their country, those union electricians assigned to the Seebees expected to have a job waiting for them after the war. The promise was implicit but by no means guaranteed. Anyhow, in 1941, there was a war to be won, so off Stehman and others like him went, proud to serve and then very happy to return home safely.

Local 48 members have served in our nation’s armed forces in Iraq and Afghanistan, during the War in Vietnam and in the Korean Conflict. They served in the Rainbow Division during World War I and worldwide during World War II, as civilians in Portland’s shipyards and in the military, especially in construction and engineering units such as the Navy Seebees. Patriotism and service remain hallmarks of Local 48.

1974 “Local 48 and Intel Lead the Way Into the Digital Age”

Intel’s Ronler complex, shown in this aerial photo taken by Randy Rasmussen and published in The Oregonian in 2012, has since been completed, thanks to thousands of IBEW Local 48 electricians.

In 1974, Oregon was still a forest products state when a start-up called Intel announced plans to build its first computer chip fabrication plant in Oregon.

That same year, a kid named Bob Shiprack was lucky enough to gain membership in Local 48 and learn the electrician’s trade on that first of many Intel projects. Like a lot of us at Local 48, Shiprack benefited from work on Intel and other high projects. During Shiprack’s career, and that of thousands of us in Local 48, Intel would become the single-largest employer of NECA contractors and IBEW Local 48 electricians in the history of union.

Indeed, between 1974 and 2015, IBEW Local 48 electricians, “travelers,” and dozens of NECA contractors found work on Intel projects and those of hundreds of other high technology companies that clustered around the high tech behemoth in Washington County.

Intel alone invested $20 billion in the most technically advanced computer chip fabrication plants in the world, all of them located west of Portland on six different campuses (Ronler Acres, Jones Farm, Hawthorn Farm, Aloha, AmberGlen and Evergreen), employing today more than 17,000 people in Washington County.

Of course, Intel wasn’t the first. There was Tektronix, homegrown in Oregon in 1948 by Howard Vollum and Jack Murdock. But after Intel’s arrival, literally hundreds of other high technology companies launched electronics manufacturing in what has become Oregon’s “Silicon Forest.” The construction created a huge ongoing demand for us at Local 48 as Oregon’s economy transitioned from forest products to the Digital Age.

In 1991, Oregon began a 10-year economic boom created by the computer industry, telecommunications and the Internet. Technology jobs increased 20%. Timber jobs declined 20%. Two years later, Oregon passed the Strategic Investment Program, enabling equipment property tax exemptions for manufacturers to fuel economic growth. It did.

In 1994, Local 48 electricians and their union contractors helped expand Intel’s operations with construction of a $705 million Aloha project, the first phase that could lead to future expansion of its microprocessor design and production facilities in Hillsboro.

In 1996, a small army of us Local 48 electricians completed work on Intel’s Fab 20 computer chip manufacturing plant near Hillsboro Stadium. The chip factory was the first of four that Intel would build, making it the largest employer of NECA/IBEW Local 48 electricians in the region. During the boom, Intel also built RA1, the first of a series of highly complex computer chip factories in Hillsboro.

NECA contractors and thousands of Local 48 electricians found opportunity with Intel, but also with 1,800 other high tech firms, including Tektronix, LSI, Fujitsu, Wacker and Mitsubishi, that through 2000 invested $10 billion in plant construction. High tech employed more than 60,000 people. Welcome to the Silicon Forest!

In 2009, the Great Recession threw a lot of Oregonians out of work. Oregon’s unemployment rate peaked at 11.6% in June of that year. Recovery would be stymied by weak job growth, and tepid construction and manufacturing through 2013, with one exception: Intel.

More than 2,000 Local 48 electricians, and travelers, and their NECA contractors found work with Intel’s construction of the fabrication facility, D1X, at the Ronler Acres Campus in Hillsboro on what would turn out to be the largest such project in the United States.

IBEW Local 48’s future along with that of its members is inextricably tied to Intel and the family of high technology companies that make Oregon and Southwest Washington home. There’s no way to know the future. The industry is complicated and getting more complicated – far more than pipe-and-wire.

Today everything is “smart,” including the electricians who make things happen for the high tech industry.

As for that kid, Shiprack, he would persevere, doing rope-work to survive the recessions of the 1980s, while advancing the cause of organized labor until his retirement, in 2010, as head of the Oregon State Building Construction and Trades Council.

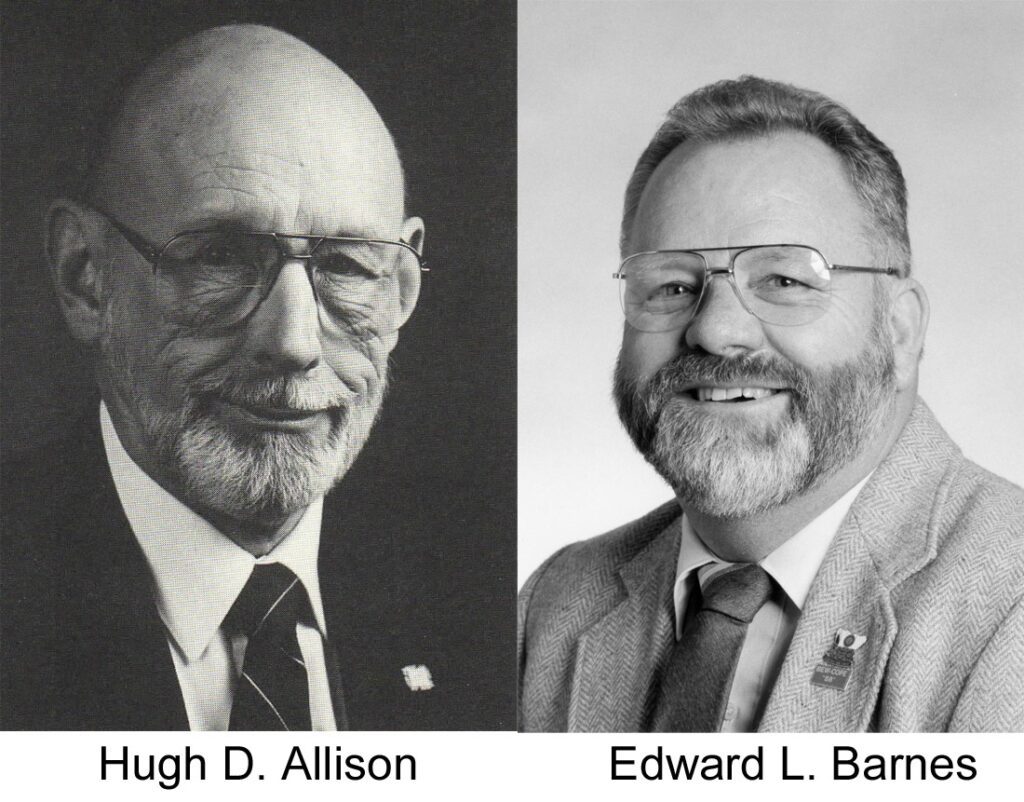

1983: “Why Is It the ‘Barnes’ and ‘Allison’ Labor Management Cooperation Committee?”

In 1983, the Oregon economy collapsed. IBEW Local 48 struggled in the economic rubble of two back-to-back recessions. A lot of workers lost their jobs. More than a few families lost their houses.

In the midst of the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression, the leadership of Local 48 reached out to NECA to launch in 1986 what today is known as the Market Advancement Program (MAP).

To regain their market share in the midst of economic disaster, Local 48 and NECA decided to focus solely on what was best for the customer. They formed a high profile Labor Management Cooperation Committee (LMCC). The task of LMCC was to educate the public about the positive partnership of Labor and Management. Today, the marketing and promotion partnership is known as the BALMCC – Barnes-Allison Labor Management Cooperation Committee.

But who were those two guys, “Barnes” and “Allison”?

The “Barnes” was Edward L. Barnes. He apprenticed as a member of IBEW Local 48 in 1955 and became its business manager in 1983. More about him later.

The “Allison” was Hugh D. “Buzzy” Allison. Like Barnes, Allison started his career long ago, before most Local 48 members were born!

Allison’s career began in 1945 when he joined Local 48 to work as an electrician in Portland’s shipyards. In 1953, Allison launched his own “high tech” business, Buzzy’s Television Shop. In 1959, he became an electrical contractor and stalwart member of NECA. During the second half of the 20th Century, he served as president of Oregon Electric Construction (now Oregon Electric Group, or OEG), Allison Electric and Sunset Electric of Oregon. He was a pivotal leader who held many positions in the Oregon-Columbia Chapter of NECA and its national body for more than a half-century, and was at the forefront of just about every union movement in the industry.

Allison not only served as president, governor and member of the board of directors of the Oregon-Columbia Chapter of NECA, he promoted hiring of women and minorities, and continuing education of journeymen during the tumultuous civil rights era of the mid-1960s. As the president of NECA in 1968, Allison championed the Metro JATC’s education of African American men, which that year included Bonnie Lewis, Bob Neal and Michael Colbert. That same year, Allison led NECA and IBEW Local 48 to fund the electrical wiring of the Albina Art Center serving some 800 families of color in the Albina neighborhood, which prefigured the long-term partnership with the NAACP and the Urban League of Portland.

In 1977, Allison spearheaded Metro JATC’s purchase of a 15,000 square foot former Safeway grocery in northeast Portland to provide classroom space for a burgeoning number of apprentice electricians. In 1989, Allison was named a Fellow of the Academy of Electrical Contracting, the highest honor bestowed on an individual by the electrical contracting industry.

Barnes, like Allison, was also active from the day he apprenticed in IBEW Local 48. After serving in the Korean Conflict, Barnes went to work in 1955 as an apprentice for Donovan Electric on the construction of The Dalles Dam on the Columbia River. By the mid-1970s, Barnes had been an active member of Local 48 for more than 20 years, inspired by his father Jennings to fill just about any leadership post that was offered by his fellow union members. During his career, Barnes worked as foreman, trustee, executive board member, union president and a dozen other leadership roles.

During the disastrous post-recession era of 1983, Barnes’ first year in office as business manager, unemployment exceeded 12 percent in Oregon. One-third of Local 48’s members were “travelers” seeking work out-of-state, in some cases as far away as the East Coast. Rather than argue over who was to blame, Barnes called on his counterpart at NECA, Tim Gauthier, who was hired just one year earlier. The two agreed to sit down and talk.

With the help from Professor Orv Iverson of Clark College in Vancouver, Washington, Barnes and Gauthier formed a plan for renegotiated wages. They conceived a new approach to health and welfare benefits, drugs and alcohol abuse. They sought to improve programs for apprenticeship and continuing education to improve the quality of workers, including women and minorities. They planned for a secure retirement for members. Their work inspired members of Local 48 BALMCC. It worked. Members of NECA and IBEW Local 48 thrived through the 1980s and 1990s. Barnes was re-elected, again and again, until his retirement in 1995.

That year of 1995, Metro JATC found itself running out of classroom space. The shortage prompted the training program directed by Ken Fry to expand into Whitaker Middle School and Portland Community College’s Cascade Campus.

In 1998, independent of the Portland school system, and any other governmental agency, the training trust invested $6 million into construction of a new NECA/IBEW Electrical Training Center, adjacent to Local 48’s offices just east of Portland International Airport. Today, under Training Director Rod Belisle’s leadership, the NECA/IBEW Training Center is meeting the demand for a diverse, motivated and highly educated workforce.

In addition to its role in promoting education, BALMCC also provided for a Code of Excellence that is inculcated at every level of the NECA/IBEW partnership. The results of the market recovery program and the efforts of the BALMCC the past 30 years have been impressive:

Allison died in 2011. Barnes remains active as a volunteer. Both serve as examples to union contractors and members alike.

In their honor, Barnes and Allison’s names were affixed to the NECA/IBEW Local 48 partnership. The honor not only represents a tip-of-the-hat for their achievements. It also reminds members of IBEW Local 48 and NECA of what is possible in their own careers.

1984 “It’s a Tough, Dirty Job — But Somebody’s Got To Do It!”

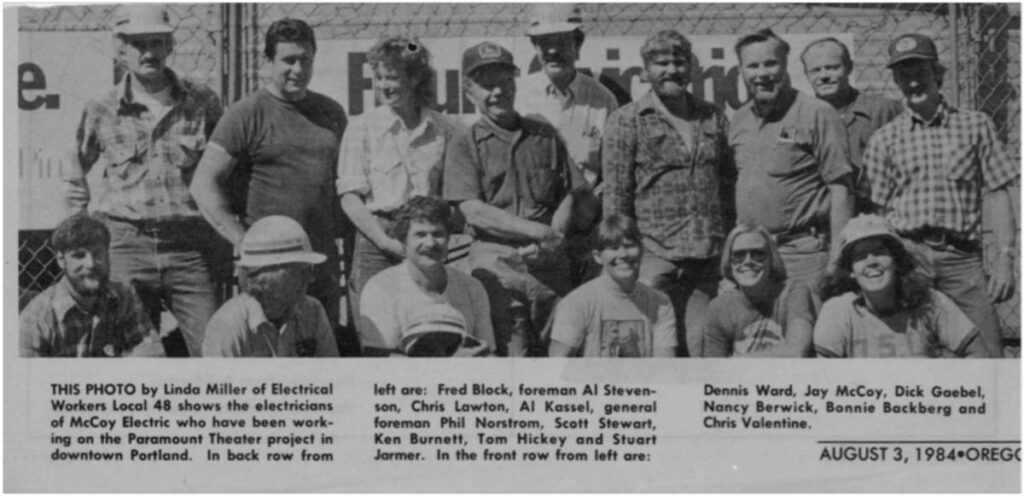

The 15 members of Local 48 in the news clipping from the Oregon Labor Press, above, are smiling now. But you should’ve seen their hot, dirty, sweaty expressions a few months earlier! But we’re getting ahead of ourselves.

This story starts back on October 6, 1979, when the board of the Federal Reserve Bank chaired by Paul Volcker hiked interest rates in an effort to cure the rampant inflation of the 1970s. The Fed action effectively froze home-building, shattered Oregon’s economy, slashed timber employment by 50%, or 80,000 jobs, and ushered in what many called a “double-dip” recession in 1980 and again in 1981.

The downturn bankrupted many NECA contractors and threw hundreds of us Local 48 electricians out of work. The economic calamity reduced the numbers of apprentices, including women and minorities, sought by NECA/IBEW Local 48.

Survival was the top priority. Union contractors slimmed their shop staffs. The hall at Local 48 was full of long faces. Members were saying good-bye, traveling out-of-state for work, some as far away as New York City. Church ministers implored Business Manager Ed Barnes to help their parishioners before they lost their homes. Everybody was suffering. But there were bright moments, rays of hope. One of them was the Paramount Theatre project.

Max and Marlene Landon had just purchased McCoy Electric, a NECA member since 1946, when the recession hit. Landon had to reduce his shop from 100 to 25 until work picked up. Fortunately, in October 1983, McCoy landed the job of renovating the historic Paramount Theater in downtown Portland. It would be dirty, dusty and relatively dangerous. But at least it was work, and it would last for almost a year for 15 to 20 members of Local 48.

At the completion of the project, five of the 15 electricians who gathered for the traditional group photograph were women. Like their male counterparts, all of the women smiled with the self-evident pride of a job well-done: Chris Valentine, Bonnie Backberg, Nancy Berwick, Chris Lawton, with Linda Miller taking the picture.

Foreman Ken Burnett credited his diverse crew for safely tearing down and restoring a structure as historically delicate as the Paramount Theatre. Massive dismantling created physical hazards and the daily hassle of breathing 55-year-old dust in crevices not used for decades was “very challenging.” He said, “It’s been an especially dirty job, but very rewarding to see history repaired and restored.”

That women comprised 20-percent of the McCoy crew didn’t impress Burnett: “They do their job just like the others.” Ditto Landon: “It doesn’t make any difference to me – I don’t care: Send me little green men so long as they can do the job, and do it right.”

Landon attributed the competence of his diverse crew, as well as that of Blessing Electric, which did the production lighting, to the education the electricians received in Local 48’s apprenticeship program directed by Dan Faddis at Metro JATC, predecessor of NIETC.

“They do a fantastic job at the Training Center. I’m very pleased with the product that we’re getting out of there,” Landon said, himself a graduate of the old Metro JATC “Apprentice School” in hot, cramped quarters at Benson High School in 1963.

As far as Landon was concerned, there wasn’t any particular lesson to be learned from the Paramount project. It was just incontrovertible evidence that a solid union contractor with a competent and diverse crew can survive the worst economic recession. Why? Because we have the training and the desire to do the toughest jobs, safely and efficiently.